I used to be one of those people who, when people said they didn’t have time to cook, would think, “Who doesn’t have time to cook?” Until that person became me. (I recently told someone that at least 30% of my life nowadays is apologizing for whatever I’ve said and done, but soon I may be bumping that up a few percentage points.)

Back in the day, Marion Cunningham was flabbergasted when people told her they didn’t have time to cook. She said, “What the hell is everybody doing then?” She was so worked up about it, that she wrote a book called Learning to Cook with Marion Cunningham, and invited people to come to her house and learn how to cook with her. (Someone actually videotaped her classes.)

I don’t have kids, but as the stay-at-home, well…whatever you call me, I’m home most of the day, so it falls upon me to make dinner. And as anyone who’s made dinner knows, it’s not just making dinner. It’s doing the planning, shopping, doing the cooking, and doing the clean-up. To this day, I don’t know how my grandmother did it, working full-time while raising four kids, and making dinner (and breakfast and lunch) every day, which was before the advent of all the convenience foods and delivery services that are available today. Plus she told me that my grandfather would also surprise her and invite a few of his friends to dinner without telling her. 😬😬

In addition to my grandmother, I also admire those people who open a cookbook and pick something out for dinner. It all sounds delicious, and fun, and like a lot of shopping. To make a lot of recipes from cookbooks, I’d have to go to three stores to, say, find orzo, pre-order chicken carcasses from the butcher to make stock (pre-made stock is still in powdered cubes here, and I’m not ready to go there), then I’d have to go to the produce store or outdoor market to get Swiss chard and herbs, then the fromagerie for the cheese, and then I’d have to make breadcrumbs. Then you have to make the recipe.

Contrary to my grousing, though, I love to cook, and even shop for food. It’s just a full-time job, and I’ve already got two or three of those. So it baffles me, and marvels me, how people who work full-time manage to get a home-cooked dinner for their family on the table every night. If you are that person, I humble myself before you.

Someone recently wrote to me, asking if I could recommend a book for someone beginning to cook. Cooking isn’t just about following a recipe. Learning to cook is also how to use your senses, not just words on a page (or computer screen), to assemble something. Why is homemade stock better than store-bought stock? Do you really need to use San Marzano tomatoes? What’s the difference between a $30 knife and a $150 knife? How to know which potato to use? And how do I adjust a chocolate chip cookie recipe to make cookies that are crispier, or chewier?

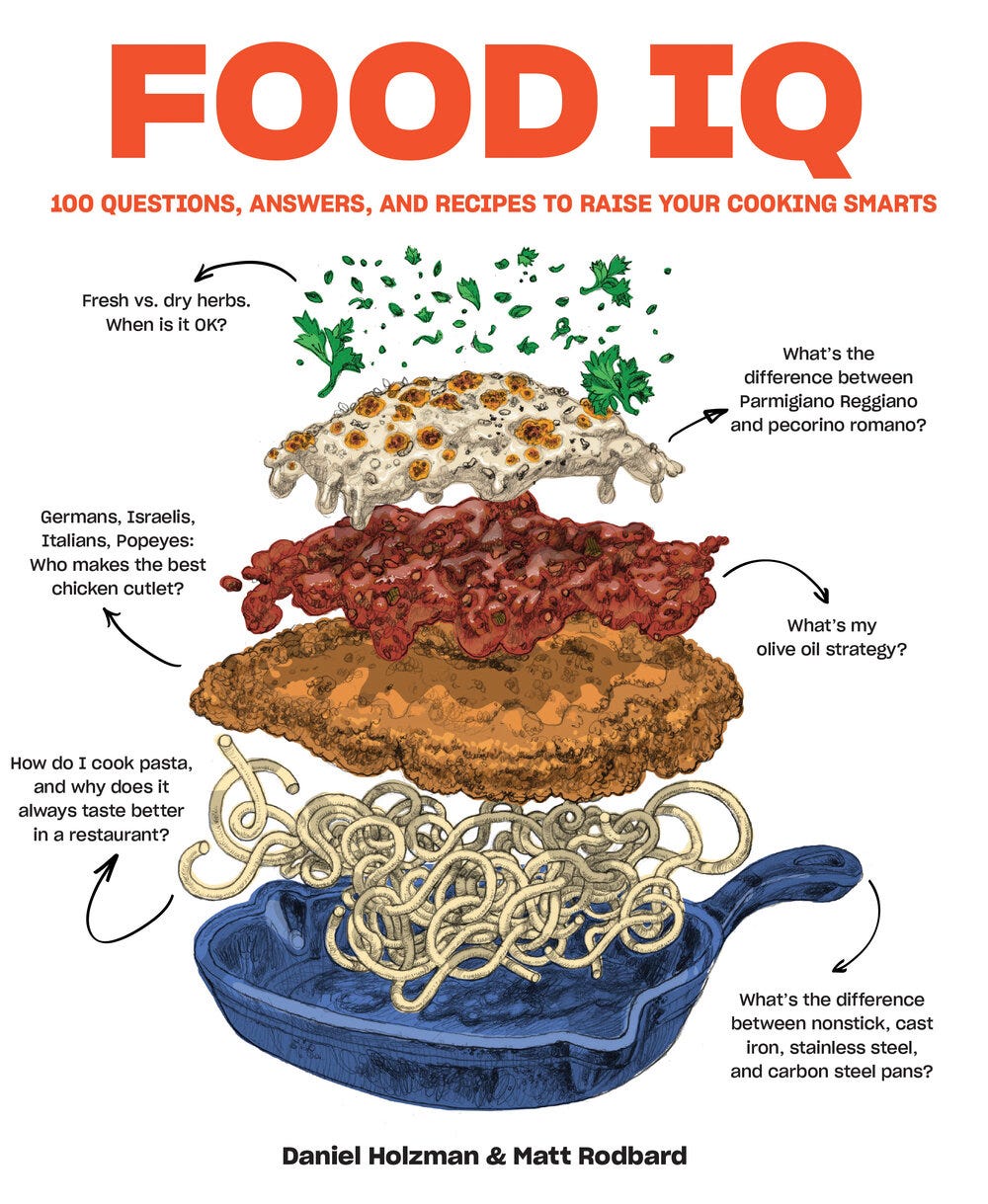

The answer to these questions, and others, can be found in Food IQ: 100 Questions, Answers, and Recipes to Raise Your Cooking Smarts, a rather fascinating, irreverent (in a good way) book by Matt Rodbard and Daniel Holzman that’s filled with cooking tips, and recipes, that teach you how to cook and bake, and gets right to the point—telling you things that you really want to know, including what you don’t need to know, or buy. Matt is the editor of Taste, and Mark is a chef who began his career at Le Bernardin and is now the owner of The Meatball Shop.

If you’re a time-pressed cook, as I am sometimes, North African tagines are pretty handy. They’re easy to make, have lots of flavor, have ingredients that you may already have in your pantry, and they’re hard to screw up. And while some say you should make a tagine in a real tagine (even the authors of Food IQ say that…), I make them all the time in casseroles and Dutch ovens, and not one person has complained.

I did have a tagine like the one above, which was made by Le Creuset. The very first time I used it, I tried to remove the very hot conical top wearing oven mitts, and the whole thing slid out of my hands and crashed down into a half-dozen pieces. They’ve since added a raised rim to the top, but I’ve never replaced it with another tagine, because, well…space.

I had almost everything in the recipe on hand; the only things I needed to get were cilantro and chicken. I know it’s a huge splurge, but I love it so much that I forgo owning a car or buying shirts at Hermès so that I can buy saffron. The best is Persian, although saffron is grown in France, Spain, Italy, Sweden, and California, if you want to keep it local. It’s important to buy it from a reputable dealer as there’s a lot of fake saffron out there. If you don’t have it, you can leave it out. (If you do spring for the good stuff, you can make tahdig, crisp Persian rice, with it.)

One stumble I did have was when the recipe said to let the marinated chicken sit overnight in the refrigerator, then simmer on the stovetop “until the marinade begins to boil.” In my kitchen, I marinated the chicken in herbs, spices, and 3 tablespoons of olive oil, which didn’t yield any liquid after marinating (above)*. I know French chickens are leaner than American chickens, and I ended up adding stock to the pot, which I usually do when making a tagine, as well as tweaking a few other ingredients, adding apricots since I like dried fruits in tagines. Prunes are delicious, too.

[*That said, I did circle back to the authors on this and they cook the tagine differently in the book than I did, placing the onions in the tagine with a bit of oil, then adding the chicken, and covering it to steam for 10 minutes, which they said would yield enough liquid to boil. I didn’t try that method but if you want to give it a go, their recipe and techniques are on page 64 of their book.]

Chicken tajine with olives and apricots

Four servings

Inspired and adapted from Food IQ by Matt Rodbard and Daniel Holzman

One time-saver, if you don’t want to chop the herbs, is to tie them in a bundle with string and just put the bundle in the Dutch oven when cooking the chicken, rather than marinading the chicken with the herbs. If you go that route, you can use the weight of the parsley and cilantro to guesstimate how much to use. (The weight chopped is without the stems, but the exact amount isn’t critical.) Or just use a small bunch of cilantro and about half a bunch of parsley; as far as I know, no one’s ever complained about a dish that was seasoned with too much parsley… Don’t like cilantro? Leave it out.

Kosher salt is also discussed in the book as some brands are saltier than others. I would use Diamond Crystal, but if using another brand, such as Morton’s, you can reduce it by half.

Four chicken thighs and legs (about 3 pounds, 1,3kg), separated if sold attached

1 tablespoon kosher or grey sea salt

1/2 cup (30g) chopped cilantro

1/4 cup (15g) chopped flat-leaf parsley

3 cloves garlic, chopped

1 tablespoon sweet paprika

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1/2 teaspoon ground dried ginger

1/2 teaspoon ground turmeric

Freshly ground black pepper

3 wide strips of orange zest

4 tablespoons (total) olive oil

1 preserved lemon, seeds discarded, pulp removed and chopped, and rind sliced

Pinch of saffron threads (optional)

1 medium onion, thinly sliced

3 cups (750ml) chicken stock (low-sodium if not homemade)

1 1/2 tablespoons tomato paste

3/4 cup (120g) green olives, pitted or unpitted

3/4 cup (135g) dried apricots

Juice of half lemon

In a medium-to-large bowl, toss the chicken pieces with the salt. Add the cilantro, parsley, garlic, paprika, cumin, ginger, turmeric, a few good turns of black pepper from a pepper mill, the orange zest, 3 tablespoons olive oil, preserved lemon pulp, and saffron threads, if using. Toss to coat the chicken with the seasonings, rubbing some under the skin. Cover and refrigerate overnight.

Heat the remaining 1 tablespoon of olive oil in a Dutch oven over medium-high heat. Add the onion slices and cook, stirring occasionally, until the onions are wilted and translucent, 3 to 5 minutes. Add the chicken pieces so they’re in an even layer, then add the chicken stock and tomato paste. Cover, and when the mixture starts to boil, lower the heat so the liquid is at a gentle simmer and cook for 1 hour.

Add the olives, apricots, and lemon rind. Press them in so they’re tucked under and around the chicken pieces. Cover and simmer another 15 minutes, or until the apricots and olives have softened a bit. Remove from heat.

To serve, squeeze some fresh lemon juice over the chicken and stir gently. Serve warm — possible sides would be couscous, barley, rice, bulgur wheat, or another starch or grain.

On learning to cook: I am 71 and have been cooking since I was 9. My husband is concerned (perhaps with reason) that I'll drop dead before him, and so he has begun to question how and why I do what I do, and sometimes cook a meal himself. The other night, he was planning to boil potatoes and brought the water first to a boil. When I realized, I said, no, you must put the raw potatoes in cold salted water. "Why?" he asked. "Because." I said. But we googled it and sure enough I am (of course) correct but I realize during this experiment that I have picked up some information over lo these 60 years.

Incidentally, with your mention of making breadcrumbs I want to share a little discovery I recently made here in France about that. You can ask your local boulanger for their breadcrumbs (chapelure) from their bread slicing machine (just ask for chapelure, you don't have to specify that it comes from that machine). Mine gives them to me for free. You'll have to sift them somewhat as some are too large, or simply smash them, but it's a ready supply of them that they may be happy to get rid of. I know some boulangeries do save theirs and make other things with them, but likely they have more than they really need. I then just add whatever herbs or anything I need to them, and they are excellent.