Interview with Food Writer Alec Lobrano

Paris-based author of My Place at the table

My guest today is Alexander Lobrano. Alec, as most of us call him, has been a vital part of the Paris restaurant scene for decades, having covered the bistros, brasseries, and restaurants in the city for publications like the New York Times, Travel & Leisure, The Guardian, Condé Nast Traveler, and most notably, as the Paris correspondent for Gourmet magazine.

I’ve gotten to know Alec over the years, sharing tables in Paris cafés, dining in bistros and restaurants, and sipping vin at local wine bars, and let me tell you - he’s definitely one of most fascinating dining companions I know, with an encyclopedic knowledge of French cuisine, and a quick wit. Interestingly, we grew up near each other but never met ‘til I ambushed him at a book signing for his book, Hungry for Paris, a comprehensive dining guide to the great restaurants in the city, a number of years ago.

In addition, Alec gloriously chronicles his meals on his blog at Alexanderlobrano.com in addition to his books Hungry for Paris and Hungry for France. And he has a new book coming out on June 1st: My Place at the Table: A Recipe for a Delicious Life in Paris, a memoir where he dives deeply into how he discovered the wonderful world of food, and how he fell in love with (and within) Paris, which came with a few ups and downs along the way, landing - enfin - in the city he has called home for three decades.

I’ll be chatting with Alec about his book, Paris, and other subjects live online with Book Larder on June 3rd. It’s free and you can sign up here!

David: Hi Alec. Thanks for chatting with me here on my newsletter. I’m so used to talking with you over a bistro table, but this year has been rather, um…challenging.

As a bit of an introduction, you’ve written two books, Hungry for Paris and Hungry for France, which are both great references to where to dine in France. As one of the most esteemed food writers, why did you decide to turn the pen on yourself, to write a memoir?

Alec: The desire to write this book just sort of dropped in my lap - like a ripe peach - but I’d been mulling it over subconsciously for a long time. I love writing about restaurants, food, and chefs, but I also just plain love writing and storytelling. My voice has developed a lot through the years, so I was drawn to doing a non-fiction project with two main characters—me and food, that would tell the story of how I became a writer who chose to make food his subject.

My book is also the answer to many people, but most of all my late father, who had asked me, “But why food?” That’s what my father said asked me the last time I ever saw him. He complimented me on my writing but found my primary subject matter incomprehensible because it didn’t seem important to him. I disagreed, of course, because for me there is no subject that’s more important than food.

Writing My Place at the Table is also the expression of my desire to push out the walls on my relationship with food and writing. Because the internet has set off an era of iconoclasm, the formal expertise I’ve acquired over more than thirty years of eating in France needs to be expressed differently in today’s food and media world, to remain valued and relevant.

David: I’ll say…and yes, the internet has really changed things. Anyone can be a food writer nowadays howeever it’s interesting how many people attempted to do so back when food and travel blogging started, but haven’t kept up with it. But you’re right; the tone of food writing has changed and evolved.

You began writing about fashion, hopping from New York to London, before finally settling in Paris. You have a chapter on a dinner you had two months into your life in the city, where at one point you realized that you were “not a tourist anymore,” which changed everything. But mostly, as a young man untethered in Paris, you were mostly dining on your own, which is something Americans are apprehensive about. What was your earliest experience of dining in Paris, how did your experience evolve, and what did you discover dining alone?

Alec: Actually I worked in book publishing and magazines in New York City for ten years before my fleeting affair with fashion, first in New York and then a second time in Paris, because of a job I went after as a way of getting there.

But insofar as eating alone is concerned, I think it’s changed some in the United States, but dining out, as in going into a restaurant and sitting down at a table alone, as opposed to being seated at a counter or standing, was something I never saw anyone do until I first visited Paris. My family went to La Coupole on that trip, and I was fascinated to see several people dining by themselves.

When I arrived in Paris to work for a fashion publisher, I knew no one, so I ate an omelette with salad in the café near the hotel I was staying in almost every night until the day the stout blonde waitress who always served me, reproached me for it. “You’re young, you have some money, you’ve just moved to this beautiful city, so go out and discover it!” she barked, and as embarrassed as I was, I knew she was right.

So the next day I bought a bunch of restaurant guidebooks and picked out a place that sounded good, Au Quai d’Orsay, which was famous for its mushroom dishes, and made a reservation just for me on the following Saturday night. I was pretty mortified when I arrived, but eventually I relaxed and had a superb meal all by myself. This little triumph left me feeling elated because it was then that I understood the best way for me to learn about Paris and improve my French was by going to its restaurants.

David: It’s funny that you were just a timid young man scared to order anything more than an omelet…who eventually because one of the world’s leading voices on French cuisine! How did you pivot from fashion, to writing about the bistros and restaurants in Paris?

Alec: The first story I ever did from Paris for Fairchild Publications was about Androuet, a famous cheese shop that was then located on the Rue d’Amsterdam. I loved meeting Monsieur Androuet and visiting the aging cellars carved into the limestone beneath the shop with him, which unfortunately are now gone. My French was terrible, but he was patient and kind, perhaps because he saw that I really was fascinated by everything he taught me about French cheese. It wasn’t until after I’d left the interview, for example, that it was explained to me by the photographer who’d accompanied me that instead of telling Monsieur Androuet that his cheeses were masterpieces worthy of being in the Louvre, I told him his cheese should be smashed on the walls of the museum; the photographer had groaned at my train wreck of a sentence, so I’d known something was wrong, but Monsieur Androuet never raised an eyebrow.

The story went over well, so I wrote on anything gastronomic as often as I could. The more I wrote about food, the more I knew I’d found my vocation, especially since I had so little interest in fashion, which was the meat and potatoes of Fairchild Publications, which published WWD (Women’s Wear Daily), W, M and a variety of other titles. Outside of my job, I began freelancing for magazines and newspapers in the U.S. and the U.K., doing chef profiles and restaurant reporting, since I knew I wouldn’t stay at Fairchild forever.

David: Androuet was one of the first cheese shops in Paris that I ever visited and I remember being completely wowed but it. I never saw so many amazing cheeses in one place! If you want to see the glory of France in one place, go to a fromagerie (cheese shop.) As you know, you can get by in France without speaking much French, but if you know the language, you can better understand French culture, French people, and French cuisine. How was that a critical juncture for you, in both your appreciation of French foods and learning French?

Alec: It’s absolutely essential to learn and master French if you plan to live in France. Otherwise, too much will go over your head, and even when you do speak French, it’s often still a real challenge to understand the country, because in this ever homogenizing world, the manners and sense of humor of the French are so different from those of the English speaking companies. In terms of manners, France is still a more formal country, and in terms of humor, there’s the inexplicable fact that they venerate the late American humorist Jerry Lewis and find him very funny. There’s no exact equivalent word in French for ‘wit’ either.

David: Interestingly, there also isn’t a word for ‘home baker’ in France either! Being a food writer and critic, part of your job is to suss out where to send people who are visiting. In My Place at the Table, you talk about suffering through a meal at the hallowed L’Ami Louis, a favorite of tourists (those who don’t mind parting with a lot of money). There was a notorious takedown of it by A. J. Liebling, plus I have friends who’ve had, shall we say, less-than-pleasant experiences there. But when you wrote it up for the magazine you worked for, your editor said it was the best bistro in the world and wasn’t pleased and told you to “fix it.” Why do you think places like that still hold their sway in Paris over tourists and some locals? And how do you balance taking on certain hallowed places that may be resting on their laurels? Do you take them on and risk the backlash, or just choose not to write about them?

Alec: There are certain restaurants that are like public/private clubs, usually for the very rich, who like to be surrounded by people like themselves. L’Ami Louis is one of them. Money is the first barrier to entry, but then there’s the whole issue of having enough clout to land a reservation since L’Ami Louis is tiny. So L’Ami Louis is a quintessential plutocrats’ clubhouse, as was the 21 Club in New York City, which has apparently just closed.

(A Note from David: The iconic 21 Club in New York was closed by its current owner, the French-owned LVMH luxury group, who plan to ‘reimagine’ the restaurant.)

These restaurants are as much of a sociological phenomenon as they are a gastronomic one, which is to say that people go to them as a rather vain rite of self-identity as much as they do to eat, which is why if I really wanted some good old-fashioned bistro food I’d rather go somewhere like chef David Rathgeber at L’Assiette and tuck into the best cassoulet in Paris.

Paris also has restaurants that are beloved by the fashion crowd and which play the same game of desire, sharpened by inaccessibility. The awful restaurant at the Hotel Costes was one of these for a long time until it stopped being fashionable, as was Dave, a mediocre Chinese restaurant inexplicably adored by the jet set, and Stresa, a very average Italian restaurant near the swanky Avenue Montaigne.

Insofar as writing about bad or disappointing restaurants is concerned, I think it’s a vital part of any restaurant critic’s work, because staying mute is not an option, especially in the restaurant landscapes of most of the world’s major cities, where most new restaurants have public relations people whose job it is to make everyone want to go to them and create a buzz about them. Public relations is an essential part of the media world, of course, but the problem arises when too many journalists are afraid to bite the hands that feed them. When I worked as the Paris correspondent for Gourmet, the magazine paid for every single meal I wrote about and I always booked and dined as anonymously as possible. Unfortunately, fewer and fewer media outlets have the budget to afford such objectivity anymore.

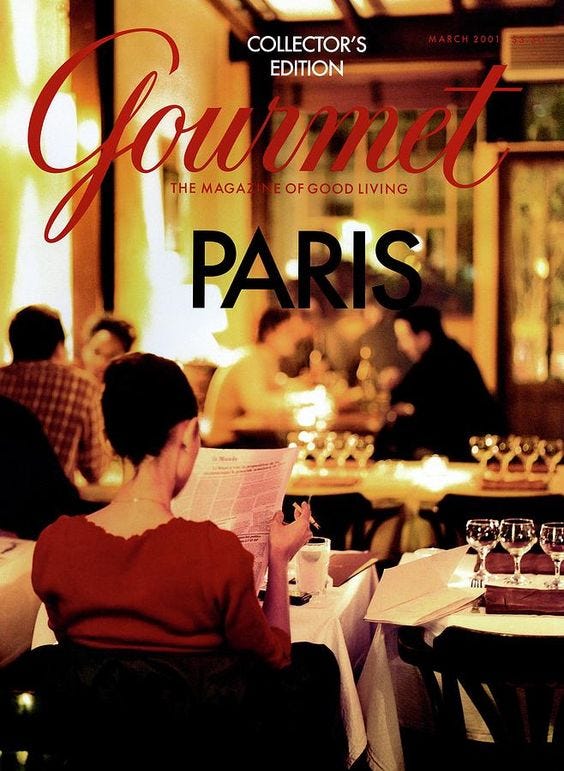

David: I can’t imagine anything called “Dave” being mediocre, Alec! But it is an unusual name for a Chinese restaurant. You were the Paris correspondent for Gourmet magazine for more than a decade, before its demise. I remember reading your columns and dreamed about someday eating at all the places you wrote about. How did you land that dream job?

Alec: Ruth Reichl, who was then restaurant critic for the New York Times, had read a profile of the Spanish chef Ferran Adrià that I’d done, and had told a woman who was a friend of both her mother and mine, to tell me that she’d like to meet me the next time I came to New York from Paris. So then a couple of months later, Ruth invited my mother to join her and Mrs. Greenberg as her guests when she went to review a restaurant. The meal was traumatic for me for a variety of different reasons, but my travails created a bond between Ruth and me. Then she moved to Gourmet, and I started writing regularly for the magazine, and since they liked my work, I was invited to become the Paris correspondent.

David: I remember the famed Paris Issue (in 2001) that came out under Ruth Reichl’s helm, which featured a woman in a chic red dress holding a cigarette at Waly-Fay bistro while perusing the menu, above, which caused a bit of a ruckus at the time. (Which was one of Ruth’s talents.) But I also remember an article you wrote about places in the outer arrondissements. You talk about that article in My Place at the Table, how the editors at Gourmet back in New York weren’t too enthusiastic about your wanting to write about places outside of the more familiar areas, like the 6th and 7th. Why did you feel strongly about profiling them, rather than the usual suspects in the center of town?

Alec: The brilliant Los Angeles restaurant critic, the late Jonathan Gold, once said to me: “Paris is to New York what Hawaii is the Los Angeles, the Never-Neverland you’re always dreaming about, and no one ever wants their fantasy tampered with.”

For generations of Americans, the locus of this fantasy Paris has been Saint-Germain-des-Pres, where I lived for ten years. This is the Paris that Woody Allen rendered in “Midnight in Paris” or Nancy Myers aced in “Something’s Got to Give.” But the gentrification of Paris is more subtle than that of New York or London, but just as tenacious. And the rise of a brilliant generation of young chefs practicing la bistronomie, or modern French bistro cooking, meant that from roughly 1990 onwards, the most interesting new restaurants in Paris weren’t opening in expensive Left Bank locations where many apartments had become pieds-à-terres for the world’s wealthy, but in outlying, previously working-class arrondissements, like the 11th and 12th in eastern Paris.

These residential districts were unknown to most Americans who loved Paris, but they were you had to go if you wanted to discover the city’s best new tables during a trip here. I really had to insist on covering this mysterious turf in that Paris issue, because as a Parisian, I knew that they were where the good food was. I got a lot of pushback from people who either didn’t believe Paris had changed, or who didn’t want it to change. I think this American meme of Paris is evolving a bit but perhaps at the pace of an escargot.

David: You were definitely ahead of your time, and kicked off the trend of going “off the beaten path” whereas now, I think diners are more willing to head to areas like Belleville and the 10th for dinner.

Alec: Oh, oui!!! I got major pushback when I suggested doing a feature on the brilliant cooking of Raquel Careña, the self-taught Argentine-born chef of Le Baratin in Belleville. I had to keep reassuring certain editors that Belleville wasn’t dangerous and that Carena’s cooking was truly worth the trek from Saint-Germain-des-Pres, to a little shopfront restaurant in a steep cobbled street in a neighborhood where no one had yet decided that the neighborhood graffiti was artistic. Once they actually ate her food, though, they raved about it, and this restaurant became a fixture in many people’s little black books.

David: I remember trekking up to Le Baratin and it seemed like it took forever to get up to the top of that hill in Belleville! But it did become a destination for many diners in Paris, thanks to you. Like a lot of people, it must’ve been a shock to you to find out so abruptly that Gourmet magazine had folded, as you talk about in your book.

Alec: It was a real gut punch, and it would have been nice to have a phone call or an email in advance, but the sky had fallen in New York, so I found out about it when the French press started calling me for comments.

David: It caught a lot of us off-guard. Gourmet really was, for many of us, one of our main gateways to France. You’ve been in Paris for more than three decades and it’s hard to explain how much the food scene has changed just in the last 8 to 10 years, especially after French cuisine took some notable hits in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Why do you think French cooking took a noticeable nosedive…and what brought it back?

Alec: I’m not sure that French cuisine actually took a nosedive, as much as the rest of the world became as avidly interested in good food and cooking as the French have always been. And then there was the inevitable temptation of idol smashing as middle-class America became interested in good food beyond the high-brow Gallic guard rails of gourmet dining that had always defined the pinnacle of gastronomy in the United States. To wit, why should French cooking be judged as better than Mexican, Moroccan, Indian, etc.?

As a country of immigrants, Americans have a pretty broad knowledge of the flavors and foods of other countries, and I think this is what changed our food culture from one that was hierarchical with French food at the top, to horizontal, with French food among the many kitchens we love, explore and reference.

Then there was the media factor, with magazines and newspapers breathlessly reporting that Spain had dethroned France, which it hadn’t because most of the Spanish chefs that were being praised had actually trained in France. Then they moved on to breathlessly reporting that Scandinavia was the new utopia for people who love good food.

For me, Spain has some spectacular food and chefs, as does Scandinavia, but no Western country has a food culture that’s as rich and rooted as France. This is because of the spectacular quality of French produce and the whole concept of terroir, or a specific food being produced according to specific methods in a specific place; the broad level of gastronomic literacy in France; and the excellence of French culinary schools like the Ecole Ferrandi in Paris.

I also think that the subtlety of French food sometimes gets lost in the noise of the contemporary food world, which loves big flavors. Here I’m thinking about chefs like Bertrand Grebaut at Septime, who does mesmerizing and deceptively simple miniatures like a roasted sunchoke slicked with freshly roasted hazelnut sauce and topped with French black caviar or rosy medallions of venison with Kerala pepper, fermented turnips and a black-garlic-spiked jus as soft and luxurious as a sable coat. This is what the best contemporary cooking is like in Paris right now, and it’s descended from la bistronomie (modern French bistro cooking), which was itself a child of La Nouvelle Cuisine. French food has been evolving non-stop ever since Michel Guerard invented la cuisine minceur and nouvelle cuisine ushered in the use of more vegetables and fresh herbs, shorter cooking times, and jus (reduced bouillons) instead of cream-enriched sauces.

This fifty-year-long evolution is why we eat so well in Paris today; because it adds a whole new category of choices to the static offer of haute cuisine, cuisine bourgeoise tables, brasseries, and bistros, the four main restaurant categories as they existed when I moved to Paris.

To be sure, the demise of Paris’s brasseries dented the city’s gastronomic reputation, as did the rising use of cost-cutting food-service company kitchen shortcuts like pre-made sauces, salads, and other dishes. But these menaces got the bad press they deserved, and now many Parisian brasseries are better than they’ve been in a long time and there’s more ‘real’ cooking going on in moderately priced Paris restaurants than ever. This is why Paris is a much more exciting place to eat today than it was when I arrived in the late 1980s.

David: Eating habits have really changed in the last few years, even before the pandemic, with younger people adopting a more casual style of dining, quaffing natural wines, ordering vegetable-centric dishes, and perhaps less steak-frites, with more dishes featuring flavors from other cultures. Restaurants like Mokonuts, Restaurant David Toutin, Rooster and Asian-accented Brigade du Tigre and Cheval d’Or have redefined dining in Paris. Over the years people have asked me to comment on the status of French cuisine, and I’m not even sure what that means anymore. What would you say French cuisine is... in 2021?

Alec: I think that even in 2021, French cuisine still has its roots in the regional kitchens of France and is piloted by the compass points of seasonality, thrift, and simplicity. The greatest and most enduring misapprehensions about French food are that it’s too rich, too fancy, too fussy, and too expensive. Most of the time it’s none of those things, as cooks and chefs like Alice Waters and Daniel Rose know and practice.

The title of a favorite book by the late Elizabeth David tells all: An Omelette and a Glass of Wine. This is a quintessential French meal, as are dishes like beef cheeks braised in red wine, blanquette de veau, duck a l’orange, etc. These are the eternal dishes of the French kitchen, but that doesn’t mean that cooking in France is static. Couscous is now one of the top ten favorite dishes in France, which shows how France’s long colonial relationship with Algeria, and then Tunisia and Morocco, influenced French cooking. And Paris is a worldlier city gastronomically than its ever been in its history because new ways of eating and types of food have been added to the restaurant scene, like rings to a tree. I mean who would have ever thought that Parisians would go insane for cheeseburgers and lobster rolls?

But today, young chefs in major cities all over the world know each other’s cooking, which is why fermentation became a thing. But it’s only in Paris that a 25-year-old chef like Alexia Duchêne would be invited by Alain Ducasse to do a three-month pop-up at Allard last October, would have sought to express her creativity by reimagining this restaurant’s famous duck roasted with green olives as a duck-filled pithiviers served with green-olive-and-walnut sauce, a brilliant idea.

David: It’s funny how many people insist that eggs and wine don’t mix. I often cite ‘an omelet and a glass of wine’ as a typical French meal, to counter that argument. (Which usually works.) Many people pine for the bistros and brasseries of yesteryear and new life has been breathed into them at places like Bouillion Pigalle, Brasserie Bellanger, etc. who do their versions of the classics at affordable price points. (Although you can run up at bill at some of the old stalwarts.) Still, most of the talk is about the younger generation of chefs forging their own identities. Are bistros and brasseries still relevant?

Alec: I think that the soul of France still lives in its bistros, bouchons, estaminets, winstubs, and all of those simple happy places where conviviality is generated by a shared love of good food and wine. So bistros and bistro cooking are as eternal for me as the great pyramids in Egypt. The brasserie is another happy Gallic invention that bloomed after so many Alsatians fled German-occupied Alsace for Paris and other cities after the Franco-Prussian war. At first, brasseries were simple brew-house restaurants serving sausages and choucroute garni (sauerkraut with sausage and pork), but they evolved into something more glamorous and metropolitan as more and more people began to travel at the end of the 19th century, leading up to the amazing boom in visitors to Paris for the Universal Exhibition of 1900.

The Parisian brasserie formula of affordable mostly short-order food, like freshly shucked oysters, steak, and grilled sole, made restaurant going available to middle-class Parisians, who also loved their elaborate decors as well as the theater of a big busy dining room. Brasseries got lost when they were bought up by the Frères Blanc and the Brasserie Flo Groupe, but as you mentioned, they’re coming back again for the great people-watching as much as the food and also because they’re so profoundly Parisian; I only wish they hadn’t become so expensive.

David: Memoirs can be tough to write, deciding what to talk about and how personal you want to get. You did a bit of both, talking about some of the difficulties in your life and the challenges, which was very courageous. Was that hard for you, or did you feel relieved to have been so open about it in the book?

Alec: When I went back and reread my finished manuscript, after not seeing it for a few months, I was shocked by some of what I’d written, because I’d been so used to hiding so many of the things I’d put down on paper. But ultimately, yes, I did feel a great relief, because after a very long journey, I’d come full circle, which means I feel quite free to do whatever I want in the future, in terms of writing.

David: When I was writing my memoir, L’Appart, you told me, “A memoir has to have a happy ending.” What was the happy ending to your story?

Alec: The self-acceptance that came from releasing the shame I’d internalized for so many years after having been abused as a child. It took a long time for me to understand, but when you put your wounds out in the sunlight, they heal. And to learn that what happened to me wasn’t my fault either.

David: Lastly, since we’re both from Connecticut: Lobster roll...mayo or warm butter?

Alec: I take my lobster rolls any way that I can get them. And if that means in Paris, I like both the Connecticut lobster roll—with the brioche roll being slicked with lemon butter before being filled with lobster, and the Classic, with chive mayonnaise, served at chef Moïse Sfez’s two Homer Lobster restaurants, one in the Marais and the other in Saint-Germain-des-Pres. But my all-time favorite lobster rolls are found at Abbott’s Lobster in the Rough in Noank, in our home state of Connecticut.

David: Connecticut proud! Thanks Alec…maybe at some point, we’ll have a conversation over lobster rolls at Abbott’s, which is my favorite, too.

Check out: My Place at the Table: A Recipe for a Delicious Life in Paris

Read more about Alec on his website and blog Alexanderlobrano.com and subscribe to his newsletter.

Thank you for the interesting interview with Alec.

It was a timely read as, my husband is in Enfield,Ct for his 94 year old mother’s birthday week. They will be going to the shore to visit Abbott’s for a lobster roll!

Just a fantastic interview. Alec Lobrano's Hungry for Paris was the next book I read after your The Sweet Life in Paris upon our arrival in Paris as a six-month lark (2009/10). And I still have Gourmet's Paris issue. My Place at the Table will be next.