Over the years, people I know have asked me about writing their own cookbook. There are so many interesting voices and talents out there, and it’s exciting that people want to share their knowledge and recipes. However, my unofficial position, nowadays, when I’m asked for advice, is that I’ll only give it if the people if they take it. (And yes, like flight attendants who ask people sitting in emergency exit rows if they understand the emergency procedure with a verbal confirmation, I require that too.)

When people have a book idea, I get down to brass tacks and give them a few realities, such as all cakes need to be in 9-inch (23cm) pans. Nope, no one wants to buy a 7 3/4-inch (19.6cm) cake pan to bake a cake…even if that is your signature cake, sold in that signature size, at your bakery.

You’ll want to write in metrics and imperial measurements, which is like writing two separate books, and also doubles the chance of errors, so you’ll need to be extra-vigilant about catching those. But most of all, you need to start with an idea that will interest an editor, one that a publisher and their marketing team will want to buy, as well as the public.

Then you have to write a proposal, which isn’t easy. Mine, for The Perfect Scoop, was 80+ pages and took me almost a year to write. It was summarily rejected by an editor, who had pleaded with my agent to have first dibs on the book, because I “…didn’t have a show on Food Network.”

🤷🏻

Then you have to write the book. As a friend who’s written several award-winning cookbooks said to me, “It’s like having a big black cloud over you for two years.” My favorite analogy was by another writer who said, “Being a writer is like having homework the rest of your life.” The other day I told someone that I can’t leave the house until March 2025 due to book deadlines, and they thought I was joking. But in case no one believes me, I am currently living on Junior Mints and ampoules of Vitamin D.

I also once spent a vacation in Sicily staring out of the window of a small room with a desk, watching everyone leave for a day-long excursion while I proofed a manuscript — pondering whether readers refer to dark chocolate as semisweet or bittersweet, and making sure that 1 cup of almonds weighs 130 grams, not 120 grams (and if five extra almonds in a recipe really make a difference?) — reading it through line by line, all 100,000 words of it.

The bottom line, despite all the Junior Mints, dirty dishes, and lost vacations, is that you write a book because you are in love with the topic and want to share that with readers. Writing is about giving, and that’s what bakers do. And that’s what writing a cookbook is all about.

Getting a book contract is a privilege. And it’s very nice of people to buy your book when it gets published, because they trust you, which is the reason you do the very (very) best job you can.

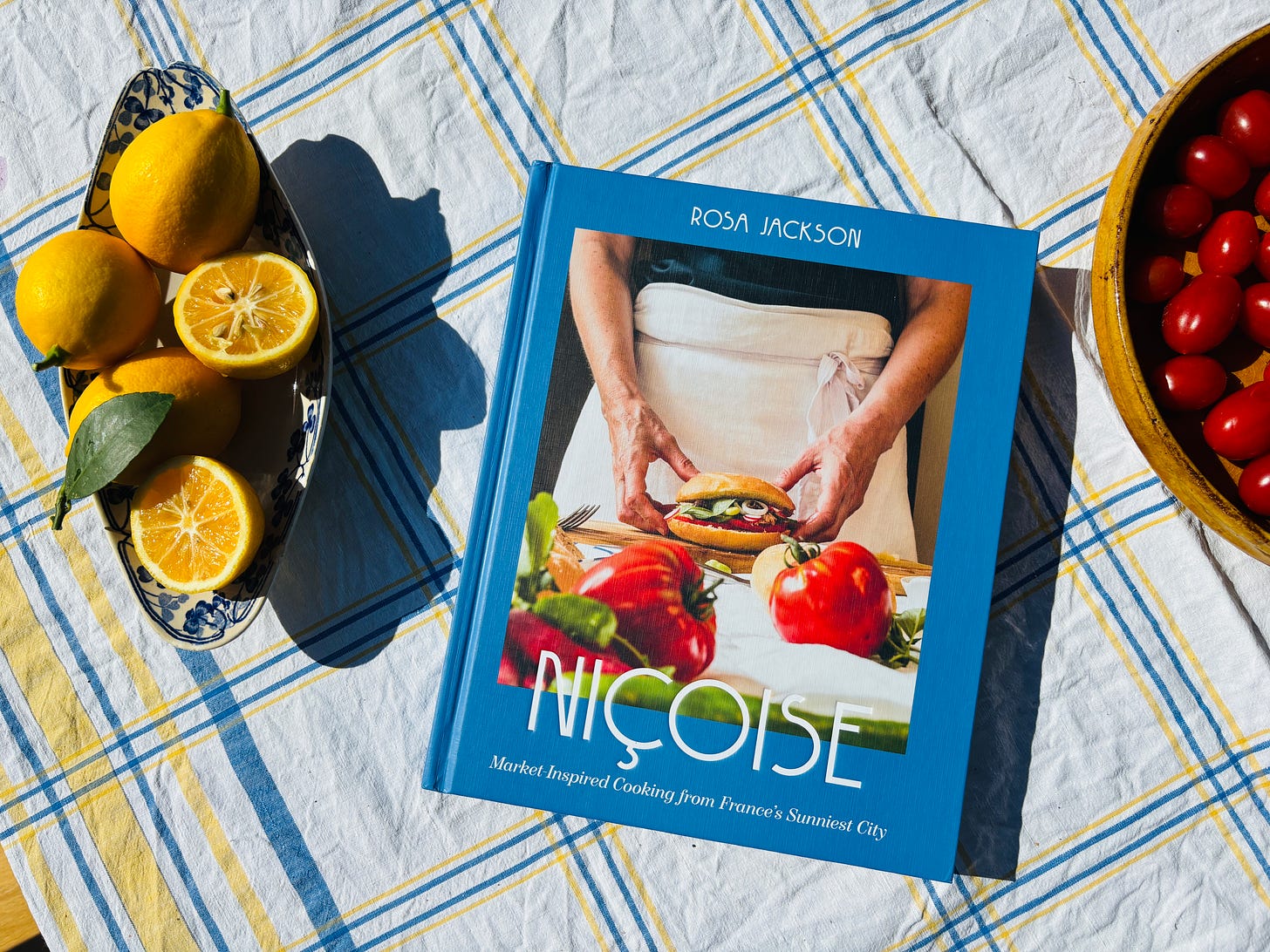

I’ve known Rosa Jackson for a number of years. She lived in Paris and edited the restaurant write-ups for Time Out before moving to Nice to open a cooking school, Les Petits Farcis, which she’s been running for over twenty years.

During one of our infrequent get-togethers, when she comes to town (and I sneak out for some real food, not just chocolate-covered mints), the subject of a Niçoise cookbook has come up. There are a handful of cookbooks out there on the cuisine, written many years ago, and I thought it was time for someone to give us a fresh, updated look at Niçoise cooking, with standards like Pan bagnat and salade Niçoise. And Rosa has the chops, and talent, to do it.

Rosa’s book, Niçoise, is subtitled “Market-Inspired Cooking from France’s Sunniest City,” which pretty much describes Nice, with its thriving outdoor market near the sea, dishes that include lots of basil, tomatoes, olive oil, vegetables, and citrus, all enjoyed with glasses of rosé under blue skies illuminated by the brilliant sunshine the south of France is famous for.

Mediterranean cooking appeals to many of us because of its focus on vegetables and freshness. Butter isn’t used nearly as frequently as olive oil is, even in desserts, such as the olive oil–enriched dough for Tourte de blettes*, a mildly sweet Swiss Chard Tart that’s unique to the region. There’s also Socca, the savory chickpea flour crêpe traditionally baked over a fire, which got a new life when chickpea flour became more available, thanks to its lack of gluten.

And who doesn’t love lemon tart? Rosa gives the classic French tarte au citron a twist with a soupçon of olive oil, just enough to give it a southern French feel, with just enough butter in there to keep it squarely French.

Even if you didn’t ask, if you want my advice, I think you’ll find that this tart is a treat any time of the year, whenever the urge strikes for a luscious, lemon-forward dessert. While some of us might be toiling away at home, or at the office, this tart will transport you to the French Riviera, even if you’re sitting in your own backyard, which is where we were when we enjoyed this. And I’m not complaining about it.

Lemon Tart with Olive Oil

Adapted from Niçoise by Rosa Jackson

For this tart, I used the last four Meyer lemons we had on our little tree. Because they are sweeter than regular lemons, I reduced the sugar in the lemon filling to 1/2 cup (100g), but if you’re using standard lemons, use 3/4 cup (150g) sugar in the filling.

I eyeballed the 1 tablespoon of zest since if you zest citrus on the counter or cutting board, you’ll lose the valuable (and tasty) citrus oils that spray who-knows-where, and I think they belong in the filling. Two lemons will yield about a tablespoon of zest, but you don’t need to be exact.

I had a tart shell in my freezer from some current recipe testing (using the recipe in my book, Ready for Dessert), so I’m sharing the recipe from Rosa’s book. Note that this is not a fill-it-to-the-rim filling, so there’s some space if you want to pipe or spread some whipped cream (or meringue!) on it, or top it with sliced strawberries or a row or two of blackberries or raspberries around the perimeter.

One pre-baked 8- or 9-inch (20-23cm) tart dough, see recipe below

3/4 cup (150g) sugar (use 1/2 cup/100g if using Meyer lemons)

2 teaspoons cornstarch

Pinch of salt

Grated zest of 2 lemons, about 1 tablespoon

Pinch of salt

2 large eggs, at room temperature

2 large egg yolks

3/4 cup (180ml) freshly squeezed lemon juice (3-4 lemons)

4 tablespoons (60g) unsalted butter, at room temperature, cubed

2 tablespoons mild-tasting extra-virgin olive oil

In a medium saucepan, mix together the sugar, cornstarch, and salt. Grate in the lemon zest and using a silicone spatula, mash the ingredients together so the flavorful oils from the zest get infused into the sugar.

Whisk the eggs and egg yolks together in a small bowl, then whisk them into the ingredients in the saucepan, then whisk in the lemon juice, until smooth.

Cook the lemon filling mixture over medium heat, stirring constantly with the whisk (to prevent lumps), until the mixture thickens and just starts to boil. When large bubbles break the surface of the filling, immediately remove it from the heat and whisk in the butter until the butter is melted. Whisk in the olive oil until smooth.

Scrape the lemon filling into the prepared tart shell and refrigerate for 1 hour, until the filling is set.

Tart Dough

Excerpted from Niçoise: Market-Inspired Cooking from France’s Sunniest City. Copyright © 2024 by Rosa Jackson. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

4 tablespoons (60g) unsalted butter, at room temperature

1/4 cup (30g) confectioners’ sugar

1 1/2 tablespoons almond meal

1/4 teaspoon fine sea salt

1 cup (120g) all-purpose flour (see Note)

1 large egg yolk

3 1/2 tablespoons delicate-tasting extra-virgin olive oil

Preheat the oven to 375ºF (190ºC).

In a mixing bowl, combine the butter, confectioners’ sugar, almond meal, salt, and 2 tablespoons of the flour and blend until creamy with a pastry scraper or fork. Add the egg yolk, olive oil, and the remaining flour. Mix again with the scraper or fork until the dough forms a smooth ball. (You can also make the dough in a food processor or a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, starting with cold butter so that the mixture doesn’t become too soft to work with.)

With your fingers, press the dough as evenly as possible into the bottom and sides of a 9-inch (23cm) tart pan, preferably with a removable bottom. (It’s normal for the dough to be very soft at this point, but if it’s too sticky to work with, flatten it with your hands to about 1/2-inch (1cm) thick in the tart pan and refrigerate for 15 to 20 minutes before proceeding.) Press the dough against the sides of the pan so that it extends at least 1/2-inch (1cm) above the rim, then cut off the excess with one swipe of a rolling pin across the top. Press the pastry lightly with your thumb all around the sides so that it comes slightly above the rim, to compensate for any shrinkage as it bakes.

Place the tart pan on a baking sheet and bake for 12 to 14 minutes, until the pastry is golden brown all over, turning the pan after 8 minutes if it seems to be browning more on one side. Remove the tart pan from the oven and set it on a rack to cool completely.

Note: My carefully-researched metric flour conversion is 1 cup flour = 140 grams, although to highlight another issue with writing in two systems of measurement, there are more chances for disputes. (Which, online, some consider opportunities.) Over the years when people have challenged and compared conversions, I advise people to use what the author says in their recipe. So in this case I’d follow her advice and conversions.

*And speaking of controversies, and discrepancies, I’ve seen Tourte de blettes also written as Tourte aux blettes.

Am definitely making the lemon tart recipe. And I actually think I remember you sitting in the room in Sicily working on edits. I definitely remember coming into that little room to say hi, and you looked frantic/miserable as you were trying to get any sliver of internet service. And 100 % endorse that feeling of a black cloud floating over your head while working on a book. Having had that particular storm cloud in my life 9 times I think I am done with it. It is HARD, and takes a toll on your daily life. Loved doing it, and as you say it's a privilege , but I'm happy these days to be writing on substack . ;)

Such an apt description of writing: “A writer has homework for life.” The cooking advice and descriptions of life in Paris are always wonderful, but this description of what it’s like to write a book is Sterling, so right on target. Having written a dozen books as a professor, the last a 5000 year history of writing, even in “retirement,” I’m still writing, tracing the path, for instance, of Charlotte Guillard, renaissance printer of Paris. Thank you for describing so accurately a writing life.