When we were shooting the photos for Drinking French in Paris, while at La Buvette wine bar, I met Kate Leahy who was co-writing the La Buvette cookbook. We were both deep in the cookbook production “zone” - she was focused on making sure the photos aligned with the text and recipes in the book while their photographer snapped away, and I was focused on getting a few seconds with the owner, Camille Fourmont, which we managed to eke in between shots for their book.

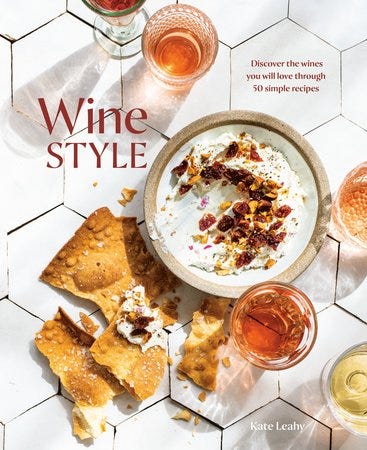

I was extra excited when I got an advance copy of Wine Style, Kate’s first solo effort, which helps people effortlessly navigate the sometimes fraught world of wine, but brings things down to the basics, and down to earth, and follows my ethos: Drink what tastes good to go. But if you’re anything like me, sometimes it’s nice to have a friendly guide to help you, and Kate is that person. Now that the book is out, I thought I’d chat with her about her life as an author, a co-author, a writer, and a former restaurant cook…

DL: Hi Kate! I remember vividly meeting you when you were in Paris, finishing the photographs for La Buvette by wine bar owner Camille Fourmont, one of my favorite wine bars in Paris. We were all buried in our project but I remember sharing a very nice moment as our book projects perfectly aligned with one another.

You didn’t begin your culinary career as a writer, though. You started your career as a line cook at various restaurants in the United States, then you transitioned to co-authoring cookbooks for well-loved restaurants, such as Burma Superstar, SPQR, and A16 in San Francisco, as well as La Buvette in Paris. (And congratulations that your first book, A16 Food + Wine, was named Cookbook of the Year by IACP and received the Julia Child first book award.) How did you make the transition from cook to cookbook co-author then to author...and an award-winning one at that?

KL: I remember that day too, David, when you were at La Buvette to shoot photos for Drinking French. That’s a good question about how I went from cooking to writing about food and wine. Maybe you felt this way in your culinary career, but I got to a point when I was still a line cook and I realized that I didn’t want to run my own restaurant. I didn’t want to be the person in charge when the dish room flooded on a Saturday night, or the sous chef quits…or essentially deal with any of the things that restaurant owners handle on a regular basis.

Long story (sort of) short, I had always wanted to write about food, so I went back to school, got a journalism degree, and worked on getting my writing back on track after years of neglect. Soon after school, I worked at a restaurant trade magazine, but my thoughts kept going back to cookbooks - especially A16, which was the last restaurant I had worked in. It just felt like I could tell a great story with great recipes with that book, especially since I knew it well after working there.

I approached the restaurant and they said “Sure…figure out how to write a book and we’ll do it.” So I did. Part of it was good timing - restaurant cookbooks were in demand, and the publisher who signed the book, Ten Speed Press, had A16 on its list of restaurants it was interested in. I basically learned how to write a cookbook by writing a cookbook. It wasn’t always pretty, but it was an invaluable experience.

DL: On your website, you have a series on writing cookbooks that cover topics like how to write recipes, how to write recipe headnotes, are all the good recipes taken?, and questions to ask yourself before writing a cookbook. Why did you feel that you needed to share that information? What was your reason for starting that series?

KL: It’s about giving back. When I set out to write the A16 cookbook, the biggest challenge was not knowing how to write a cookbook! So I relied on my new journalism skills to start asking around, finding people who could answer my questions. And I got lucky - Ten Speed was a small publisher at the time and was open to working with new (and inexperienced) authors. People helped me find my way in this intimidating industry, so I thought it was time to write up a few posts to give others a bit of guidance. If it helps people figure out what to do next, or answers a question they’ve had on their mind, it’s worth it.

DL: You co-wrote a book on Lavash breads, and the aforementioned co-authored books for Burma Superstar, SPQR, A-16, as well as a cookie book with pastry chef Mindy Segal. How do you translate “chef” recipes for home cooks? Speaking from experience, and as someone who’s worked in restaurants, chefs and restaurant cooks are known for sometimes using exotic or other ingredients not available to home cooks (which I sometimes call “…add a 1/4 cup of squab stock” problem with some chef recipes), and often their recipes are technique-driven, rather than just mixing ingredients together. How do you deal with those challenges?

KL: I think you’ll appreciate this, David. My aunt once overheard me talking on the phone about a recipe. She nearly spit out her coffee when I asked “Is the Douglas fir optional?” As soon as the call ended, she asked me what the heck kind of recipe had Douglas fir as an ingredient?

Those kinds of reality checks are invaluable when working on restaurant cookbooks. The more I do cookbook collaborations, the more I push my co-author to respect the time and resources of the home cook. If there is an ingredient or technique that will cause 99% of readers to skip the recipe, I ask if it’s really essential to the overall story…and if it is, then I make that clear in the headnote and also try to find other places in the book for easier recipes. If a chef loves a special piece of equipment that most people don’t have, I’ll test out alternatives to make the recipe with more common pieces of equipment.

I have also learned the hard way that calling for things like Champagne vinegar or muscovado sugar instead of white wine vinegar and brown sugar can mean a lot of people will never make the recipe. It’s always better to be flexible as long as it doesn’t compromise the end results.

DL: I agree 100%. I think it’s good to tell people when they really need to use something, and when it’s an option. (In spite of that, and as much as I know some people need to avoid certain ingredients, I still have people asking me if they can swap out ingredients. It’s hard to tell them that I worked hard on the recipe to get it to where it is but I encourage people to try out their own substitutions, especially if they have food allergies, and let me and others know in the comments on my blog as to how it worked out.) But a lot of time I’ll give people the option and use words like “preferably” or “optional” in an ingredient list, since I don’t like deal-breakers in recipes. Although I still avoid anything deep-fried at home, since I think those are best left to pros with professional deep-fryers…and strong hood fans.

You co-authored the Burma Superstar cookbook. Burmese cooking isn’t so well-known in the United States (or France), where the focus tends to be on Thai cooking. How were you able to translate the food served at a small - and quite unassuming - place in San Francisco, with a cult-like following, for home cooks?

KL: The crazy part about that book is that there weren’t any recipes written down for any of the dishes. Cooks trained on the job by watching, and repeating. So I had to do the same when writing the recipes for the home cook.

First I’d go to the restaurant early before the lunch cooks arrived and the head kitchen manager would lead me through a handful of dishes. I’d write it all down by hand, go home, and try it out. What I learned was that a lot of the recipes were easier to make than I initially expected because they had been modified over the years to use ingredients that were easy to get in California. Like yellow onions for all of the curries and stir-fries.

Another thing about the recipes is that many of the curries and soups were adapted to the restaurant from home cooks. So I reversed it. With the coconut chicken curry, the cooks would open a bunch of large cans of coconut milk and reduce it down separately before adding it to the chicken. They did this to make sure the curry was thickened without overcooking the chicken. At home, one can of coconut milk reduced down just fine, directly in the same pot with the chicken. I took out the extra step of reducing the coconut milk first and got better results.

DL: From Italy, Burma, and San Francisco, to France, how did you get connected to Camille at La Buvette to write the La Buvette cookbook? It isn’t just a cookbook, though, it’s also a memoir of how she got involved in the French food and wine world, and eventually opened a pocket-size wine bar which fortunately, is close to where I live.

KL: That came through a connection with Ten Speed Press. At the time, Emily Timberlake was an editor there and had visited La Buvette on a vacation to Paris. She loved it and thought it would be a great book. So she reached out and asked if I’d be interested in writing it with Camille. Camille had a U.S. agent, so all of us got on the phone and talked a bit about the possibilities.

To be honest, at first I wasn’t sure I was the right person. I live in San Francisco and I hadn’t been to Paris in years. But we had a lot of back and forth (and phone calls), and the project had potential. Eventually, we finished a proposal and got the book deal. I met Camille in person for the first time in November 2018 when I arrived for one of a couple of trips to research and write the book.

DL: To readers, it likely sounds like a dream to work on a project like that. (And even to me, I’d love to have a talented co-author on my side!) What was the experience like? Did you follow her around to tastings and to flea markets? (I know she’s a big fan of flea markets.)

KL: I did! I would sit on the back of her Vespa and she’d take me all over the place. I’m not very experienced in the world of flea markets, and to be honest I think I would have been a bit intimidated by Les Puces (the sprawling flea market in the north of Paris) — it’s enormous! But Camille was a great guide. Because our time in person was limited, we had to pack a lot into a short amount of time, and I am grateful Camille was such an organized person. She had a clear idea of where we needed to go and arranged everything so when we were there, we didn’t have much downtime.

I know it was not easy for her to always have a shadow following her everywhere, but without that time together, the book wouldn’t have been the same. As for me, I tried to stay focused and asked a lot of questions. They say there’s no such thing as a dumb question, and it’s true. But I think I asked a lot of dumb questions. Maybe being American, I could get away with it more easily.

DL: I hear you on that last bit. I’ve asked what I think are dumb questions, but sometimes you need to do that if you don’t understand something. France can be a challenge to navigate; it’s beautiful and the food is great, but not everything is evident. I actually learned a lot when I was leading tours from guests, and I continue to learn from comments on my blog and in my newsletter.

You were fortunate to get an insider’s view of Paris through a true parisienne. Are there things you learned about the city, and about wine, from her, that you didn’t know?

KL: Yes. For example, I had no idea how the wine bar culture in Paris had evolved. The idea behind a cave à manger - wine shop for eating - was new to me. I wished American cities had the same culture; the idea that you can have a small place that serves wine as long as you also get a small bite to eat. I loved that Camille introduced me to people she credited for popularizing these caves (wine bars and shops) that focused on natural wine, like Nadine Decailly, who had a place called Au Nouveau Nez for years down the street from La Buvette. It has since closed, and (last I checked) Nadine now works at Le Cadoret, which is a really lovely bistro.

DL: Since I live in the neighborhood, I walk by it and it still may be open, but usually I’m focused on getting an Algerian pastry at La Bague de Kenza, or bread and pastries at M. Jacques, just down the street, so I can’t confirm.

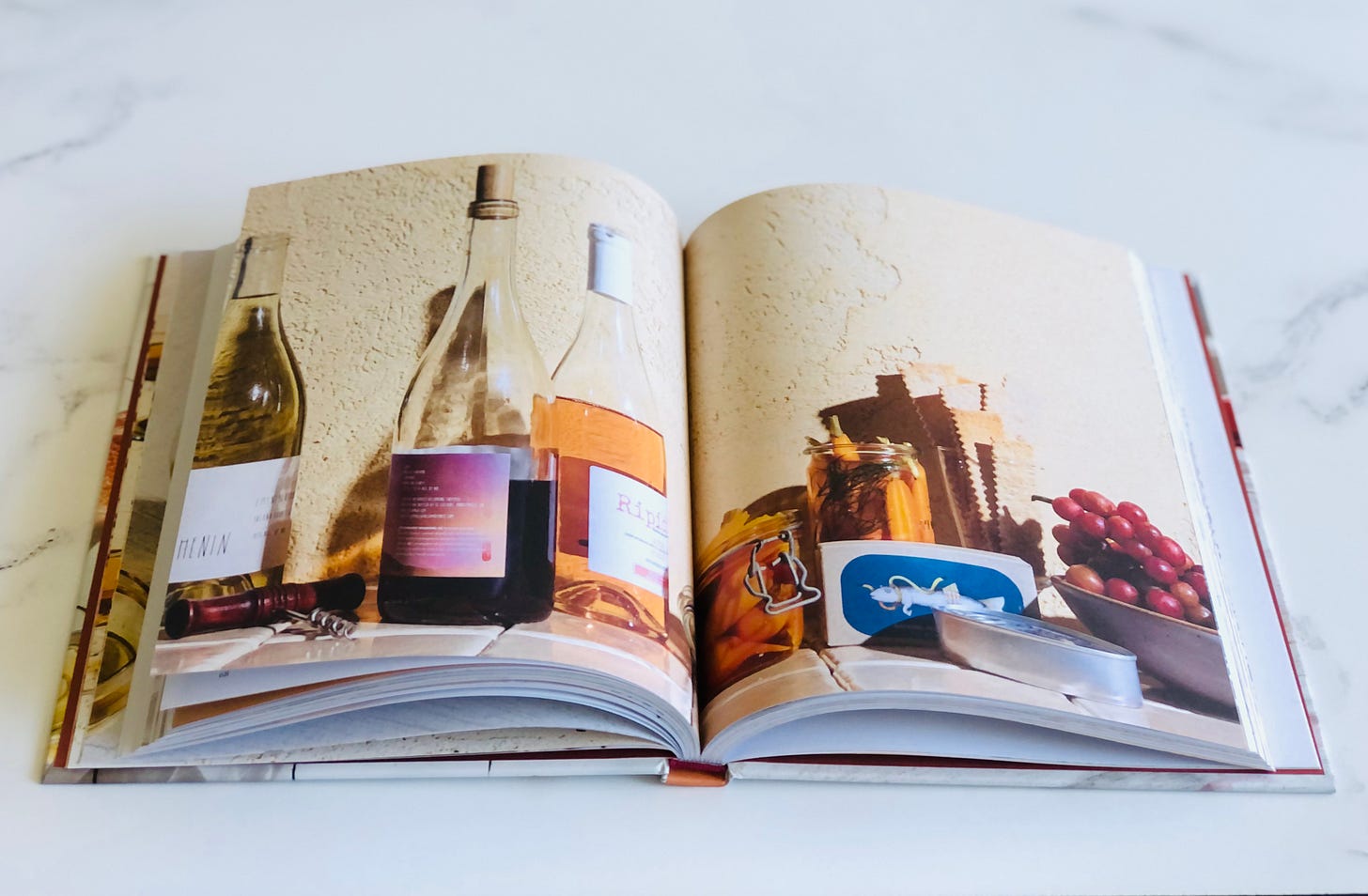

But I’m excited that you’re finally written your own book: Wine Style, with the subtitle: Discover the wines you love through 50 simple recipes, which is spot-on. It’s both a wine guide, where you talk about how to buy wine, and how to enjoy it, as well as present fifty recipes for what to eat with it. Food is so important in France so it’s great to have all those apéro and other recipes, to snack on with a glass (or bottle) of wine.

KL: That’s right, David! It’s definitely a simple wine guide for people who also like to eat.

DL: I recently read in the NYT about a woman named Mary Taylor, who is attempting to “demystify wine” by bottling and marketing wines with easy-to-understand labels, selling them at consumer-friendly price points. One of the things I love about Wine Style is how you are also demystifying wine. I think that’s so important. People have a lot of misconceptions about wine; that it’s expensive, wine people are snobby, it’s intimidating to buy a bottle of wine in a shop, or that you’re going to make a mistake when ordering a bottle in a café or restaurant. I like that you, and her, are working to change that.

KL: Mary is hitting on something that I see a lot, too. There are a lot of people who want to drink better wine but find it hard to know how to navigate wine shopping if they’re not an insider.

DL: That’s why I was surprised, and delighted, when I got an advance copy of Wine Style - it was so approachable and friendly, and took the pretense away that can intimidate people buying and drinking wine. You start the book off with wine basics, in clear, easy-to-understand terms, explaining how grapes become wine, the difference between “Old World” wines versus New World wines, and tons of helpful tips on how and where to buy wine, as well as how to store it. You packed a lot of very useful information into the book while keeping it fun to read, lively, and as I mentioned, very approachable.

KL: Thanks, David, that means a lot.

DL: I don’t think some readers realize that space is limited when writing a book (book contracts specify things like the number of pages and words, as well as how many recipes are in a book), but I think it helps us authors whittle things down to what’s really essential or important to include, which makes for a better book.

Romain, my partner (and others) was surprised when I said that I was going to write a book about French drinking culture, spanning from café au lait and chocolat chaud in the morning to apéritifs and cocktails in the evening. But cookbooks aren’t just recipes; they also teach and help us understand a culture better, allow us to share stories, and take us to other places, all of which I wanted to do. What made you decide to write a book about wine, and wine-friendly food, for your first solo outing?

KL: That’s a good question, David. In a way, I’ve unintentionally been working toward this kind of book. My first book, A16, had a large section about southern Italian wine. La Buvette had essays about some of Camille’s favorite bottles and how she learned how to taste wine. Through these experiences, I saw that there was a lot in the world of wine that had changed since I started working in restaurants and writing about food.

When I worked in restaurants, no one was talking about orange wine, or pét nat, or even rosé. A lot of the books about food and wine were older and skipped these categories. Recipes were mostly focused on European flavors with the occasional nod to Asia. So I thought that I could contribute a book that helped someone like me make sense of it all while also reflecting on what’s happening in the wine world today.

DL: Je suis d’accord! There are some esteemed wine books out there, but for someone like me, I just need to know the basics to help me appreciate wine a little more than I do, which Wine Style definitely does.

In related news, I knew a French sommelier who wanted to write a book on terroir for Americans, which I told him, frankly, might be a tough sell. (For readers who aren’t familiar with terroir, it’s about the confluence of factors; environment, weather, soil, conditions, history, grape variety, etc., that contribute to the taste and culture of wine.)

I can’t speak for all Americans but I think many wine drinkers in the States are focused on the taste and enjoyment of the actual wine, rather than an in-depth look at the conditions that it took to grow the grapes. But maybe I’m wrong? What do you think about that?

KL: It’s a fascinating question, and I’d say you can market a book on terroir, but only if it’s focused on an area that is world-famous. Or if you illustrate real-world examples of what terroir is and how this wine is different from that wine mostly because of terroir (and have tasting notes/examples). That could be a fun (though very challenging) project. David…if you have an idea how to tackle it, let me know!

I worked with Peter Liem on his book, Champagne, and his premise focuses on how Champagne shows terroir, even though many of the wines are often blends of grapes that represent different vineyard areas. Another approach is writing about terroir in an academic/university press kind of way, like Ian D’Agata did with his book Italy’s Native Wine Grape Terroirs. At that point, you know you’re going for the inside-baseball wine geeks who are passionate about understanding their wine down to each granular detail.

The tricky thing for me about terroir is that you can only understand so much from a distance. In the park across the street from me, the side closer to the San Francisco Bay is slightly cooler, so in the spring, the blossoms last longer there than the side farther west. That’s pretty much the terroir of my park. If it were a vineyard, the warmer area would be harvested before the cooler area. The best winemakers build this attention to detail into their work, but writing about it can make you sound like a weather expert.

DL: I’ve learned so much about wine (and cheese) by simply visiting the regions where they’re made. It tells you so much when you’re passing through vineyards, meeting winemakers and tasting wines, and eating in local restaurants, and you start to understand why what you’re drinking is a product distinctly of that region. Pivoting a bit here, is there anything that bothers you about the wine world or wine books and writing in general? (Or specifically?)

KL: My brain can go into knots really quickly with wine descriptions. There are a lot of adjectives that I’d never use for food, but they’re flung around with abandon when talking about wine. Like a wine whose taste imparts a “granite sensation.” I’m pretty sure they’re trying to say the wine has a pleasant mineral flavor note, not that it’s a new dance craze. It is hard to talk about how something tastes, but it is easier to follow the plot when people use descriptions that are also used with food.

Another thing that’s a bit annoying is when wine people describe a wine as masculine when it has a lot of tannins or feminine if it feels softer. This is an old-fashioned way to think about wine, and fortunately it is getting less common.

DL: It’s true, some of the language is a little dated, but part of it is because in the French language, some words are masculine, such as le vin, whereas la crème is feminine. So a chocolate gâteau can be served with sa (her, referring to the cake’s) cream. They’ve been wrestling how to keep the language au courant.

When I wrote Drinking French, I had limited space to talk about the far-reaching range of French drinks, from café au lait to apéritifs, digestifs, and snacks. As you know, the world of wine is a huge subject which I talked about but didn’t delve too far into since other books, such as yours, are devoted entirely to the subject and have the space it deserves (and needs) to handle it. The wine world is truly HUGE and I love how you packed so much information into such an easy-to-read format, and book.

KL: I know, David, the wine world truly is huge. The best part is that there’s room for everyone to find wines they like and learn more about. I drink a lot of Italian wines because I know more about them, but maybe someone out there has been exploring Chilean wines with abandon and has made some amazing discoveries. David, I have sticky notes all over your section on French Apéritifs because they’re fun and a nice bridge between the wine world and the cocktail world.

DL: There are so many French apéritifs that are iconic around the world, but a lot of people don’t know that much about them. So it was fun to dive into them and explain them in simple language so people might be encouraged to try them.

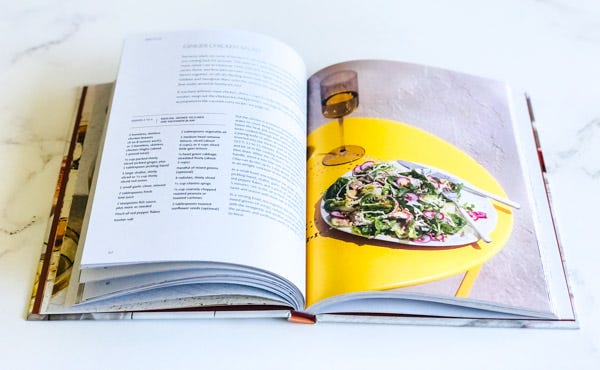

In Wine Style, the recipe chapters are broken down into what kinds of wines to drink with what, such as Crisp White Wines and Rich White Wines, as well as Orange wines, Rosé, Picnic Red Wines, and Reasonably Serious Red wines. How did you learn so much about wine? Did you already know a lot about it?

KL: Some of it I knew, but I also had to do a ton of research. I found podcasts to be a fun alternative to books, though I have several stacks of those, too. Even though I’ve never worked the floor of a restaurant as a sommelier, I’ve been fortunate to be a fly on the wall at a lot of wine tastings. Shelley Lindgren, the owner and wine director of A16, has also brought me along on some epic Italian wine trips, where we spent most of our time with winemakers and their families. After a while, you look back and realize how much you gleaned.

On the format of the book, I organized the chapters to make it easy for skimming. If you had a bottle of crisp, white wine, like a Sauvignon Blanc, you could flip to that chapter. Or if you had recipes you wanted to try, you could read the headnotes and get ideas of which wines to shop for.

DL: A number of apéritifs are wine-based, and although you didn’t focus on them in the book, are there any that are your favorites?

KL: If I could do it over again, I’d have an apéritif chapter, but fortunately I have your book so I can use it instead! When I was in college, my parents made me believe that a kir royale was quite the sophisticated choice, so maybe that’s why I am still partial to wine-based apéritifs with some sparkle, whether it’s a spritz of some sort or Lillet with club soda or tonic - or even sparkling wine. I feel there’s a lot more room for me to learn about apéritifs, which all seem to have intricate histories of their own. I still don’t think I’ve ever tasted a proper pastis, but I’ve always been fascinated by it after reading A Year in Provence a million years ago.

DL: How do you like to drink them?

KL: Now that people are finally getting together more frequently again, I’d say I like drinking them with other people - they’re just a bit more special. I think apéro hour is also one of the best ways to entertain when you’re not used to having people over. Make a couple of easy snacks, offer a couple of simple aperitifs, and have fun catching up.

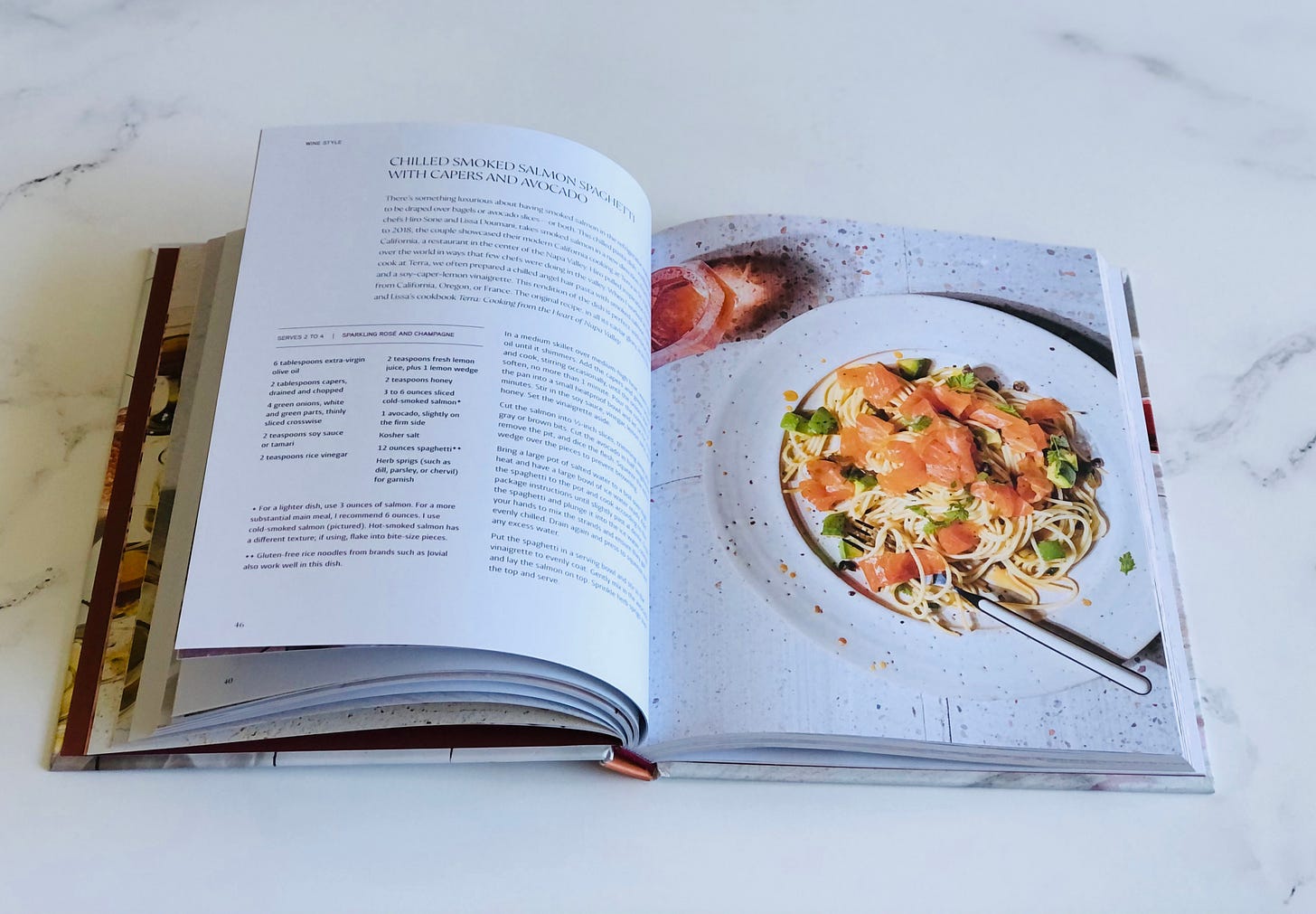

DL: Since you brought it up, let’s talk about food! There are 50 delicious-looking recipes in the book, everything from homemade crackers, chickpea fries, and eggplant lahmajoon (Armenian flatbread) to oil-packed tuna with olives, potatoes, and lemon, green olive tapenade, and fennel biscotti. All of them are easy enough for any home cook to make, and indeed, would go really well with any apéro or apéritivo party. I truly want to try them all! How did you decide which recipes to put in the book?

KL: When I started, I made a spreadsheet with a column for recipes, and a column for wines. Then I went through a dozen wine/food pairing books to see if I could find a pattern in flavor/wine pairings. This was easier for the older books, that could just say “Merlot.” The newer books had a much broader variety and included a lot of wines I had never tried, like Blaufränkisch, a red wine from Austria. For the wines that were new to me, I shopped for them to try them and see where they fit in among my chapters — Were they generally lighter style wines, or richer? It wasn’t always a clear-cut case, but I used my best judgment. And some of it turned out to be experience, playing with flavors in my kitchen. Cumin and coriander seeds went surprisingly well with a range of the orange wines I tried, while Verdicchio was really good with ginger. That last one I might have discovered after the book was edited, but I’m still learning and having fun with wine and food matches.

Ok, time for a speed round: What would you drink with…

...Potato chips

Cava

...blue cheese

Sauternes

...mountain cheese (such as Comté or Gruyère)

Chenin Blanc

...goat cheese

Sauvignon Blanc

...brownies

Banyuls

...Steak-frites

Syrah

...a cheese omelet

Pét nat

...waffles and fried chicken

Champagne

...a Croque monsieur

Pinot Gris

...peanut M&M’s

Lambrusco on the sweet side

...pepperoni pizza

Montepulciano

...a box of dark chocolates

Port

...Thanksgiving dinner

Deep pink rosé, like Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo or Tavel

...Kate’s birthday

Fiano (an Italian white from southern Italy and Sicily)

DL: Lastly, what are some of your favorite places to eat and drink in Paris?

(In no particular order)

La Buvette (of course!)

Septime la Cave (I could never get into Septime)

DL: Thanks for taking the time to chat Kate! And à santé!

KL: Thanks for taking the time to ask! A santé to you, too!

Links:

Check out Kate Leahy’s books (will link to the page on your website)

Photos in this newsletter post from Wine Style, by Erin Scott

Thanks for subscribing to the newsletter!

This Q+A with Kate is for all subscribers, If you’d like to get extra posts, recipes, interviews, and stories, upgrade to become a paid subscriber at the link below…

Thanks for the tip, David. Will definitely check out this book.

Also congrats on your ginger cake being featured in yesterday’s NYTimes article about Amanda Hesser’s new edition of the NYTimes cookbook.

And thanks for the giggle from the intro to your interview.

Eek vs. eke. To eke is (1) to manage with difficulty (to make a livelihood), and (2) to make something last by practicing strict economy. The word is usually embedded in the phrasal verb eke out; for example, one might eke out a living by selling cookies and picking up change off the street. Eek is a noise one might make upon seeing a spider ...

I’ll have to purchase this book. Sounds amazing. Have you tried any of the recipes?