I love revisiting favorite recipes of mine, even if it causes some people to freak out a bit. The trouble with having a blog/website, and now a newsletter, is that something you made 15 years ago might change, and people want to know why. Tastes change, people change, and some things become more available; not that long ago, you might have had to search far and wide for cocoa nibs, blood oranges, chickpea flour, and freekeh in America, and now I see them on supermarket shelves here and there. Plus, I learn from readers’ comments on what works and see how they put their own spin on recipes when they share them on Instagram.

Most of us aren’t stuck in time, and we evolve, change, and adapt to circumstances. And before the two-way communication of the internet, we didn’t have to explain ourselves

One example: Back in San Francisco, I used to make my morning coffee with a drip machine until I thought it would be sophisticated of me to use a French press. Unfortunately, I had a few accidents with it while pushing down the plunger, which caused the pot to slip and fly across the counter, sending hot coffee grounds and scalding water everywhere—which is the last thing you want to wipe up at 7 am. I also realized that the coffee was heavily caffeinated from steeping so long and was giving me the shakes.

A few years later, when I went to the espresso-making school at Illy in Trieste, Italy, I asked one of the scientists there what he thought about the French press*. He looked a little baffled and said, “I don’t know what that is…but the name scares me.” French coffee isn’t (or wasn’t, at the time) especially known for its fine flavor, especially to Italians, and I recall the woman at the Italian tourism office in Paris telling me, “Here, I drink tea.”

So I switched to the Italian classic, a Bialetti moka pot, which I used for a few years until I got an induction stove and switched to an induction-friendly moka pot, which prompted some questions about my allegiances. I don’t think I’m likely to switch coffee makers anytime soon, although my 20-year-old ice cream machine could probably use an update…just in case you were wondering, if you see a new one in my future. Which I would like to see, too.

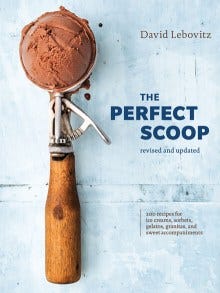

When I got to update The Perfect Scoop for its 10th anniversary, I decided to nix a few flavors that didn’t seem to be fan favorites, such as Parsley Ice Cream and Rice Gelato, with popular newbies such as Tin Roof Ice Cream with chocolate-covered peanuts and fudge ripple; S’Mores Ice Cream with marshmallows, chocolate, and graham crackers; and Caramel Corn Ice Cream. I also added a few frozen “slushie cocktails,” such as Frozen Gimlets and a Negroni Slush that you don’t have to share with the kids.

I kept the basics in place, including the Philadelphia-style Chocolate Ice Cream, which I didn’t realize was as popular as its custard-based counterpart until I posted a picture of it recently on Instagram and people let me know how much they enjoyed it. I hadn’t made it in a while, but when I dug my spoon in, I realized what I had been missing. It has a deep, dark, bittersweet chocolate flavor and is easy to make since it requires no tempering and cooking of eggs. It was perfect.

Unsweetened chocolate used to be tough to find in France, and it’s not even called chocolat — it’s often labeled as pâte de cacao (cocoa bean paste), which is precisely what it is. I was at Metro a few years ago, a Costco-like store that’s open only to professionals, and found a hefty 5kg (11-pound) block of it, so I bought the whole thing and was set for a while.

What’s interesting is that people tell me that in the U.S.** everything is too sweet, even though unsweetened chocolate is a staple in many of our pantries and not generally used in France. And to my American-raised palate, Kouign amann, macarons, and pastries like escargots, merveilles (deep-fried beignets), and pain Suisse (glazed sugar buns filled with gooey custard and chocolate chips) test my tolerance for sweet, which is pretty high, although I never turn down Kouign amann. And while French people often complain that macarons are too sweet, I don’t see them turning those down either.

The original recipe for this Chocolate Ice Cream called for a little over 2 cups (500ml) of cream and 1 cup (250ml) of whole milk. One big question I get about ice cream is “Can I lower the amount of cream?” A few things help make ice cream scoopable, namely sugar, fat, and alcohol. I hate to be Debbie Downer, and I do try to keep those things to levels that aren’t over-the-top but still taste good - but no one wants hard, dry, flaky ice cream.

However, I did give it a go last week, swapping out some of the cream with whole milk and while it was just fine, I still preferred my original version. But if your taste leans toward the leaner, I’ve given instructions in the headnote for that version.

Chocolate Ice Cream

About 1 quart (1L)

Adapted from The Perfect Scoop

In France, unsweetened chocolate is called pâte de cacao, sometimes with 100% on the label, which refers to the percentage of cocoa mass in it. You can find it in Paris in bulk at G. Detou. You can also find it in supermarkets, baking supply shops, and natural food stores. Internationally, Lindt makes a 100% bar, as well as a 99% bar, which’ll work here, too.

To make a leaner version, use 1 cup (250ml) heavy cream and 2 1/4 cups (560ml) total of whole milk. In the first step, heat the cream with 1 cup of whole milk, then add the remaining milk in the second step.

Although I’m a big fan of my ice cream machine, people have been making ice cream long before the advent of electricity, and you can make ice cream without a machine.

2 1/4 cups (560ml) heavy cream

1 cup (200g) sugar

6 tablespoons (50g) Dutch process cocoa powder

Pinch of salt

6 ounces (170g) unsweetened chocolate, chopped in small pieces

1 cup (250ml) whole milk

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

In a medium saucepan, whisk together the cream, sugar, cocoa powder, and salt. Bring the mixture to a low boil, whisking occasionally. Just as it starts to boil, reduce the heat to a steady simmer and whisk the mixture constantly for 30 seconds.

Remove from heat and add the chopped chocolate. Whisk gently until the chocolate is completely melted, then gradually whisk in the milk and vanilla.

Pour the mixture into a blender and blend for about 30 seconds, until smooth. Chill thoroughly, then freeze in your ice cream maker according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

(Print version above)

*Even in France, if you say “French press,” no one will know what you are talking about. It’s a cafetière à piston. There’s some controversy about who designed it, two Italians…or a Frenchman who came up with the idea when making coffee, who also had an accident involving his morning coffee pot. Like anything, it’s your cup of coffee, and if you like your cafetière à piston, you can and should keep using that. Just watch out for those flying hot coffee grounds!

**Many years ago I entertained the idea of creating a Salted Caramel Hot Chocolate mix using the fleur de sel sold at my local market after I became friends with the vendor. Because caramel is inherently sweet, in order to balance the hot chocolate, the base was made with unsweetened chocolate. But the idea became too complicated, as was international shipping. Fifteen years later, I finally got a chance to publish the recipe, available to all, in my book Drinking French.

…although I did get a message from someone who said it was odd that I’d put recipes for chocolat chaud (hot chocolate) in a book on French drinks. Despite my previous statement that I do take into consideration comments and questions I get when updating recipes and books, I’m not taking any of the hot chocolate recipes out in case I get to revise the book for its 10th anniversary. So there.

When I was a kid, I was food obsessed (and overweight) and I was always looking for things to eat. When I found the “baking chocolate” the first time, I was thrilled to have found a treat simply available in the pantry. And then I took my first bite. I felt deeply betrayed that there was a chocolate that didn’t taste good.

I remember Baker's baking chocolate from when I was a kid. Sweet, semi-sweet, and unsweetened. I remember the rectangular yellow (brown?) box and how you could break up the squares, making it easier to sneak a piece because who remembers how many squares were left. Mostly we used unsweetened to make brownies, but you then had to add sugar. What is the purpose of unsweetened chocolate if you then have to add sugar? Is it to get a stronger chocolate flavor or percentage?

I can't keep chocolate in the house because one bite leads to polishing off the whole lot. I guess that's a case for only stocking unsweetened.